Originally published on April 4, 2024

Last week the Dissident Right magazine IM1776 published a debate between two pseudonymous twitter personalities (Benjamin Braddock and Kruptos—representing the pro and con sides respectively) on the question; “Are Christianity and Vitalism are compatible?” One must imagine both Paul and Nietzsche rolling in their graves at once here. In any case, this debate—which has been brewing on the right for several years now—represents an interesting ideological bellwether. As such, a careful treatment of the debate can serve as a starting point for clearing away a deep confusion that has plagued a “Dissident Right” movement, which otherwise prides itself on savvy cynicism and ideological demystification.

The readership will forgive me if the tone of these reflections seems unsympathetic or severe. A surgeon must often wound in order to cut to the root of a disease and begin the process of healing. So it is with cultural matters as well, and this is a procedure for which I am not aware of any anesthesia—that would require more time than we have at present. One of the great tragedies of our age is that the best of our people—those with the best instincts and greatest intentions—through no fault of their own fall under the sway of illusions that nonetheless must be dispelled if we are to overcome the challenges of our age. No one can leap over their own shadow. Nonetheless, duty bound, we must prepare the ground for a real future for Western Civilization, even if this work is not always pleasant (that which forces us to think rarely is…).

Before getting into the meat of this discussion, it would behoove us to define the key terms at the outset. “Vitalism” is effectively the view that the fundamental problems of life (and politics) are physiological. It champions the pursuit and cultivation of excellence within embodied human existence—both in breeding and in everyday practices such as diet and exercise. Inasmuch as society is beset by various socio-political ills, vitalists analyze this from the perspective of sickness and health. The leading contemporary proponent of this view has been Bronze Age Pervert. A few quotes selected from his magnum opus Bronze Age Mindset are presented for the convenience of the readership:

I am concerned with the subjection of life and the suffocation of vitality. I hope to show you that things don’t need to be this way, and that you don’t need to limit yourself to small things. Above all you must reach for the great aim, physical and military independence. Only the warrior is a free man. […]

People at all times try to domesticate each other. Language is used to clobber and deceive others into submission and domestication. Ideas and arguments and stories are manufactured for the same. The modern world is no different in this regard from any wretched tribal society. I’m sure that Europe prior to the Bronze Age, before the coming of the Aryans, was similar to modern Europe. People lived in communal longhouses and were likely browbeaten and ruled by obese mammies who instilled in them socialism and feminism. […]

The modern world is a killjoy, in short. But the ancient Greeks were quite different, and different also from the over-serious stuffy men with English accents who play them in period dramas. What they admired was a carelessness and freedom from constraint that would shock us, and that upsets especially the dour leftist and the conservative role-player. […]

Modern “democracy” is totalitarian and vicious, and tries to subject the best to the rule of the heaps of biological refuse and most especially to the rule of those who can stir them up. […]

Here is my vision of the true justice, the justice of nature: the zoos opened, predators unleashed by the dozens, hundreds….four thousand hungry wolves rampaging on streets of these hive cities, elephants and bison stampeding, the buildings smashed to pieces, the cries of the human bug shearing through the streets as the lord of beasts returns.

—Bronze Age Mindset

BAP famously draws heavy inspiration from the vitalistic existentialist philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The philosopher Peter Sloterdijk once characterized Nietzsche’s ruthless skepticism as stemming from a “vitalistic cynicism.” So we can be assured that this is not a term that has sprang newborn from BAP’s twitter account within the last 10 years—even if he must be credited with repopularizing and revitalizing it.

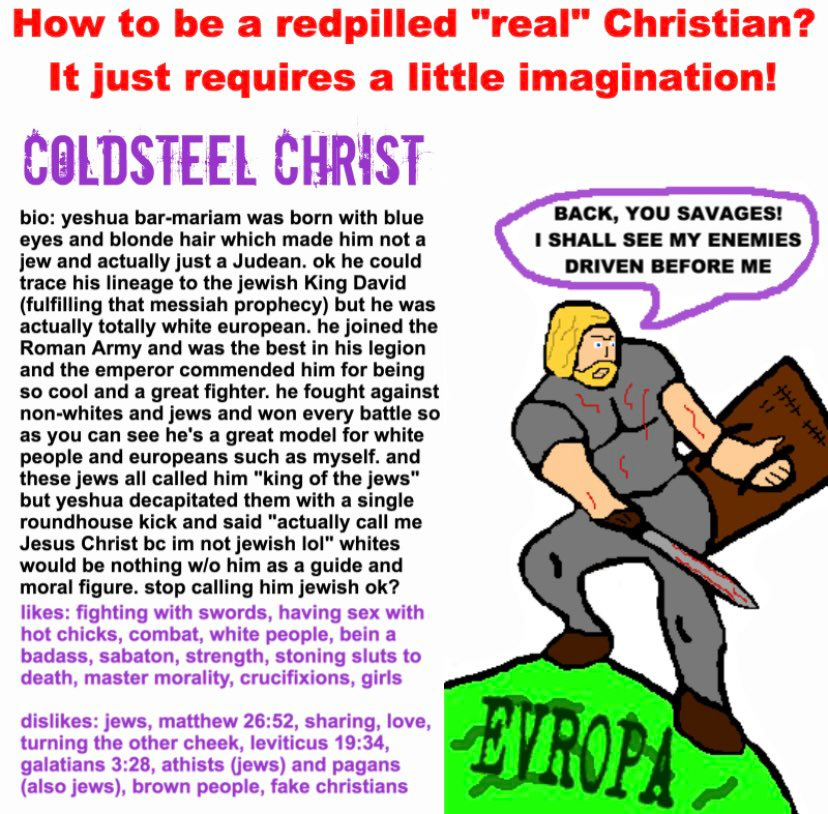

“Christianity” proves to be a far slipperier term to define. Everyone thinks they know more or less what Christianity is, in broad strokes. The primary necessary condition of being a Christian is that one has to believe that Jesus of Nazareth is God, or was the Son of God, or something to that effect. Other than that, things get murkier from here. One must, of course, consult the Bible in order to get a full accounting of what precisely it means to be Christian. However, few Christians (or non-Christians for that matter) are in the habit of doing this. So there is an extremely broad range of received opinion regarding what constitutes “real” Christianity. Many of these views are contradictory and mutually exclusive. Today as much as ever, in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, scripture often serves as a Rorschach test for one’s own political preferences. Every position under the sun, from “God’s pronouns are they/them” to the “Christian Identity” defenses of “muscular” Christianity such as those parodied in the following meme can be found:

It will be my thesis in the present reflections that any serious accounting of what it means to be Christian places Christianity in direct opposition to any “vitalist” project. Nietzsche happens to agree with this thesis—so there’s that.

Rabbi David Wolpe had an interesting article published in the Atlantic last Christmas that deserves careful consideration here. Rabbi Wolpe has a much clearer read on the situation than many right-wingers who find themselves torn between vitalistic sentiments and a need to defend our Judeo-Christian heritage. The newly emerging “vitalistic” trends are associated (correctly) with the old “pagan” veneration of nature. And herein lies the fundamental contradiction of “Christian Vitalism.” The Judeo-Christian worldview positioned itself originally as explicitly anti-pagan in every respect (indeed, the term “paganism” itself means nothing other than a non-Abrahamic worldview or way of life).

The question, however, is not whether beliefs can lead us astray, as they all can, but what sorts of beliefs are most likely to lend themselves to respect for human life and flourishing. Should we see human beings as virtual supermen, free to flout any convention, to pursue power at any cost, to accumulate wealth without regard for consequence or its use? Are gold toilets and private rocket ships our final statement of significance? Or is it a system of belief that considers human beings all synapse and no soul, an outgrowth of the animal world and in no way able to rise above the evolutionary mosaic of which everything from the salmon to sage is a piece?

Monotheism, at its best, acknowledges genuine humility about our inability to know what God is and what God wishes, but asserts that although human beings are elevated above the shackles of nature, we are still subordinate to something greater than ourselves.

If we are nothing but animals, the laws of the jungle inevitably apply. If we are all pugilists attacking one another in a scramble to climb to the top of the pole, the laws of the jungle still apply. But if we are all children of the same God, all kin, all convinced that there is a spark of eternity in each person but that none of us is superhuman, then maybe we can return to being human. —David Wolfe, “The Return of the Pagans”

It is difficult to suppress a hearty chuckle at the notion that “monotheism, at its best, acknowledges genuine humility about our inability to know what God is and what God wishes.” If one takes this statement to its logical endpoint one comes to the bizarre conclusion that Rabbi Wolfe considers the monotheism of the Abrahamic faiths to be monotheism at its worst. A bizarre opinion for someone of his profession, to say the least. But that’s all neither here nor there.

Judeo-Christianity sees itself as a necessary “moral” corrective to the barbarism of mere Nature (i.e., Rabbi Wolpe’s “laws of the jungle”), which Yahweh has placed man (or, at least, a particular part of it) above by breathing his spirit into him. It is difficult to imagine an ideology in greater contradiction to the Vitalism championed by Bronze Age Pervert—who seeks to place man back where he belongs, within nature:

You are not at bottom your intellect, this is impossible, although this is the assumption of almost all modern people even when they claim otherwise. They pay lip service to “supremacy of the desires,” or to biological determinism, but they still believe they are their intellects, just imprisoned by flesh and matter and genes and a biological “programming.” This is wrong! —Bronze Age Mindset

Inasmuch as this is all the case, “vitalism” should be seen as an attempt to recapture the natural instincts of Western man: instincts that were originally repressed and smothered by the Judeo-Christian conquest of Rome (and the priestly usurpation of vitalistic, aristocratic values) some 2,000 years ago.

We are now in a position to turn our attention to the debate between Dr. Braddock and Mr. Kruptos. In doing so, we shall be provided with an opportunity to clarify the theme of the antagonism between Christianity and Nature. Ultimately, this will provide us with an opportunity to consider the status of Christianity as a presumably right-wing ideology. Is Christianity right-wing, in principle? Or is it only relatively right-wing, as a result of the contrast between it and today’s secular progressivist culture?

The debate begins with Kruptos repudiating Vitalism as being un-Christian as such. The question of whether a worldview can be sustained or built on mere aesthetics is touched on. Perhaps this is a legitimate objection to much of today’s right-wing Vitalist discourse. At the same time, one of the main strengths lies of Vitalism in the defense of Beauty as something objective, which tells us something deep about nature, and our relationship within it. Kruptos considers this new Vitalism to be a vain and nihilistic vision, which leaves nothing behind other than having lead a “beautiful life.” Dismissing the value of such pursuits, Kruptos objects that no bodybuilding surfer boy would ever build something like a cathedral. Perhaps there is something to be said for this point. What monuments such as cathedrals represent is the will of a civilization to establish something lasting—to pass down the glory of its material and spiritual culture for generations to come. The temples of ancient Greece and Rome also represented a similar projection of the collective will deep into the future, as well as being important sites for communal ritual and worship (of the gods and goddesses—and of nature). In the Greco-Roman classical world, no contradiction can be found between the naturalistic values espoused by Vitalists and the communal religion. The cosmos was considered sacred and eternal. In the pre-Christian Western religions nature was sacred, just as much were the gods and goddesses—who often served as guardians or representatives of various natural forces and cycles. But I digress.

Today, things like nominalism, rationalism, science, technique, and the machine, cut us off from God, from the symbolic, the archetypal, the spiritual world all around us. We have closed ourselves off from God, and in many ways, this has made him functionally dead to us. As painful as it is to accept, Nietzsche was not off base in his critiques. And if writers like McGilChrist or Joyce are correct, and I think that they are, the changes that have occurred because of modernity have rendered us less able at a physical level to sense and apprehend God. Because of this functional materialism, we try to satisfy our need for connection with the transcendent by embracing our emotions. We look for the “high.” Whether that emotional high is found in a theatrical style worship service that intentionally manipulates our emotions, or it is the feeling of being in top physical condition, the rush of catching the wave, the thrill of the high-speed descent on a mountain bike, the pleasures of sexual intercourse, or something as mundane as that latest vacation in the Caribbean, we look to fill that void with the experience of vitality.

These bugbears of “nominalism, rationalism, science, technique” and so on are indicative of a highly intellectualized, philosophical Christianity—typically indicative of a Catholic education. This form of Christianity is itself an alteration from the vehemently anti-philosophical and anti-intellectual Christianity of the early church. When in the mid to late medieval era the Catholic church began permitting once again some study of philosophy in service of theology, this was a regression back to pre-Christian modes of thought. The incorporation of Aristotle and Plato by St. Thomas Aquinas was a victory of the re-paganization of the Church.

Of course “God is dead,” but it is precisely this Christian religion that was unsustainable and has lead us into this situation. It cannot bring us salvation here. If we are to rediscover the “archetypal, spiritual world” it will have to be from a fundamentally post-Christian stance.

Dr. Braddock attempts to square the circle here, insisting that Vitalism and Christianity are in some way compatible. The crux of the argument here, (at the risk of over generalizing) is that the Bible contains a “vitalistic” message insofar as it condemns Western Civilization as “Satanic.” There may be something to his reading here, however, it is ultimately biblically flawed. It is not civilization as such that the Bible condemns. Braddock principally leans on Old Testament scripture in order to make his case. It is a valiant effort, but unfortunately it falls short of the mark of accuracy. The Old Testament, in its condemnation of figures such as Nimrod and others, is not some sort of BAPian exhortation to a piratical, vitalistic anarchism. Rather, the Bible’s “anti-Civilization” sentiments must more accurately be viewed as setting “traditional” aristocratic civilization in contrast with the priestly oligarchy of the Levites. It is difficult to think of a more brilliant example of the sort of regime of domestication by endless nagging and pointless rules criticized in Bronze Age Mindset than what one finds in the Bible—especially, and, in particular, throughout the Old Testament. Time does not permit an in depth elaboration of this hypothesis from scripture, but anyone who seeks satisfaction on this point need only consult the books of the Torah (the first five books of the Bible) or 1 Samuel.

Close attention should be paid in particular to the theme of Kingship in 1 Samuel. In desiring to have a worldly King, so that they may achieve worldly glory on par with the other nations, the Israelites are depicted as rejecting Yahweh as their ruler (in reality, they are rejecting the rule by priesthood). Nonetheless, even in the transition to a traditional monarchy, everything ultimately remains subordinated to the “rules” of the Levitical priesthood. Saul is only declared King because he is chosen by the head priest in a ceremony specifically staged to appear as though the god of Israel Yahweh had chosen him from among the crowd (it is arranged earlier on between Samuel and Saul that this outcome will be so). Finally, Saul is portrayed as a “bad” King on the basis of his not following every nit picking rule of the Levitical priesthood down to the letter (these rules for monarchs the priests are helpful enough to write down in an extensive book for Saul’s consultation). We could go on at length here, but this example alone is enough to give a taste of the ultimate political orientation of the Bible. Its contents are not “anti-civilization.” Rather, it represents a new paradigm of civilization where vitality and success in war do not determine power, but priestly instincts and capacity for nagging and belaboring byzantine sets of rules. One can judge for oneself whether or not this message is compatible with “vitalism.”

“Your descriptions are stirring, in part because we can both place them within a transcendent order. The vitality we experience in this life lifts our eyes heavenward to God our Creator.”

Kruptos, ever the pious Christian, is seen here again and again asserting that, to borrow Nietzschean terms, life must be devalued, “vitalism” can only become “Christian” in this context if it is in some way directed into service of the Christian ideology—which places all value in a transcendent “beyond” where superstitious minds are told the reward for their misery and suffering in this life await concealed beyond the veil of death.

But herein comes the rub of “vitalism” as a philosophical stance. I agree wholeheartedly that civilization drains the life out of a living culture, largely in the pursuit of money and power. Spengler’s insights ring true in this regard. What happens to a culture when it self-consciously reaches the Nietzschean moment of declaring the death of God? This is the fruit of civilization. The danger that I see in vitalism in this context is not something that is rightly ordered, rooted in culture and the faith that helped birth it; rather, it lives within the dead husk of something once living, struggling for life. It sees the banal ugliness of civilization and is rightly repelled. But rather than looking to the true living source of all things, its eyes remain trapped within the experiences of this life. Desire is good when it is rightly ordered, and it is rightly ordered when its end is directed to God the Creator in Christ. This end is the key.

And this is precisely why there can be no “Christian Vitalism,” why “Vitalism” in the full Nietzschean sense of the term is a repudiation of nihilism (a nihilism which ultimately stems from Christian origins), and a call to be faithful not to the idol of a corpse on a cross—but to the Earth!

It is not Vitalism that has made life meaningless. It is precisely this ideology that there can be no value other than through the cult of the Nazarene which devalues all other values. In the name of making all mankind “equal” before the god of Israel, the value of all men is dragged down to a vacuous “zero” or nullity. This is what has fundamentally given birth to this situation of nihilism, a process the Christian notices only when this most uncanny of guests finally devours the only thing he permits himself to place any value in—the idol of Christianity.

“The church is not suffering form an excess of vitality.” Braddock retorts, and good riddance at that. However, what is overpowering today in the absence of a strong “muscular” Christianity today is the sickly shadow cast by this dead god on the West. The mainstream right and even the wokest left wing radicals remain locked within the labyrinth of the rotting corpse of this Judeo-Christian God. The true value of vitalism is that it can show us there is a world that is possible outside this labyrinth by placing our value back where it belongs, immanently in this world—not exclusively in some fabled afterlife of servitude to the Hebrew Messiah at the expense of slandering the value of life. Did the Creator bring us into this world merely to have us repudiate it?

Vitalism is in many ways an attempt to revive the pre-Christian values of the glorious Greco-Roman classical West. This fact puts the contradiction between Vitalism and Christianity in even greater contrast. After all, what was Christianity itself but an attack on precisely this well-bred vitality of the Greco-Roman civilization? Was it not Tertullian, the early Church father, who put it best, when he asked “What has Jerusalem to do with Athens?” Was it not Paul who wrote the following in 1 Corinthians 1:27-9:

“ Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things—and the things that are not—to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him.”

Kruptos summarizes his position with the following remark:

I don’t disagree that people lack vitality. My point is that I see vitalism as dangerous if pursued as an end unto itself. A vital, healthy life is both subordinate to and finds its source of power in the Living God revealed to us in the scriptures.

In all of the endless discussions of Christianity in today’s Dissident Right there is little effort put into sorting out whether Christianity is true or not. This is natural enough. Conservatives see Christianity and Christian institutions as the only thing we have that could possibly fill the moral and spiritual void of our era. So then we must defend it. But this is merely a reactive standpoint, in which the right finds itself defending a fundamentally egalitarian, anti-vitality, anti-hierarchical ideology, simply because it is older than the latest iteration of these same errors. The moral and political clarity the right stands to offer as an alternative to the madness of the secular humanist liberal egalitarian (i.e., “woke”) projects is undermined when it takes up the cross. Consider the “He Gets Us” ads that caused no small amount of consternation in our circles during this year’s Superbowl:

Here is a taste of what a life “subordinate to…the Living God revealed to us in the scriptures” looks like. These ads were not paid for by any subversive “woke” elements within the Church. They were paid for by the owner of Hobby Lobby—a longstanding boogeyman of the “reddit atheist” community for its stance as a privately owned, explicitly Christian corporation. I encourage anyone who doubts this to feel free to consult the words of scripture for themselves and draw their own conclusions. For a consistent, post-Christian Vitalistic meditation on these issues, Nietzsche’s The Antichrist remains the definitive treatment of this subject.

Vitalism, in its philosophically developed form, is a re-affirmation of Natural Law and the priority of our natural endowments (created or otherwise) against the nihilistic, social constructivist madness of both the blank slatist anarcho-liberal-communist left and the Christian conservative right. We must return ourselves to our own common sense, which, rather than drawing power from what is “revealed” in Scripture, has been plagued for millennia by precisely these foul texts. Pious platitudes in defense of a “right wing” Christianity can only seriously be enunciated today without squinting too closely at these supposedly sacred texts. The Poetic Edda and the works of Hesiod are much better candidates for divinely revealed scriptures—not to mention much more in line philosophically with the newly emergent “Vitalist”right. Although, strictly speaking, it must be admitted, Vitalism as such implies no particular religious orientation, it is agnostic on metaphysical matters, and purely concerned with the value of this world. Rather than being a weakness, this is precisely why it serves as a torch to help us through this transition through the darkest twilight of planetary nihilism, to that which must emerge on the other side—if we are not to be totally destroyed by the collapse of our Judeo-Christian heritage.